Let's mix again!

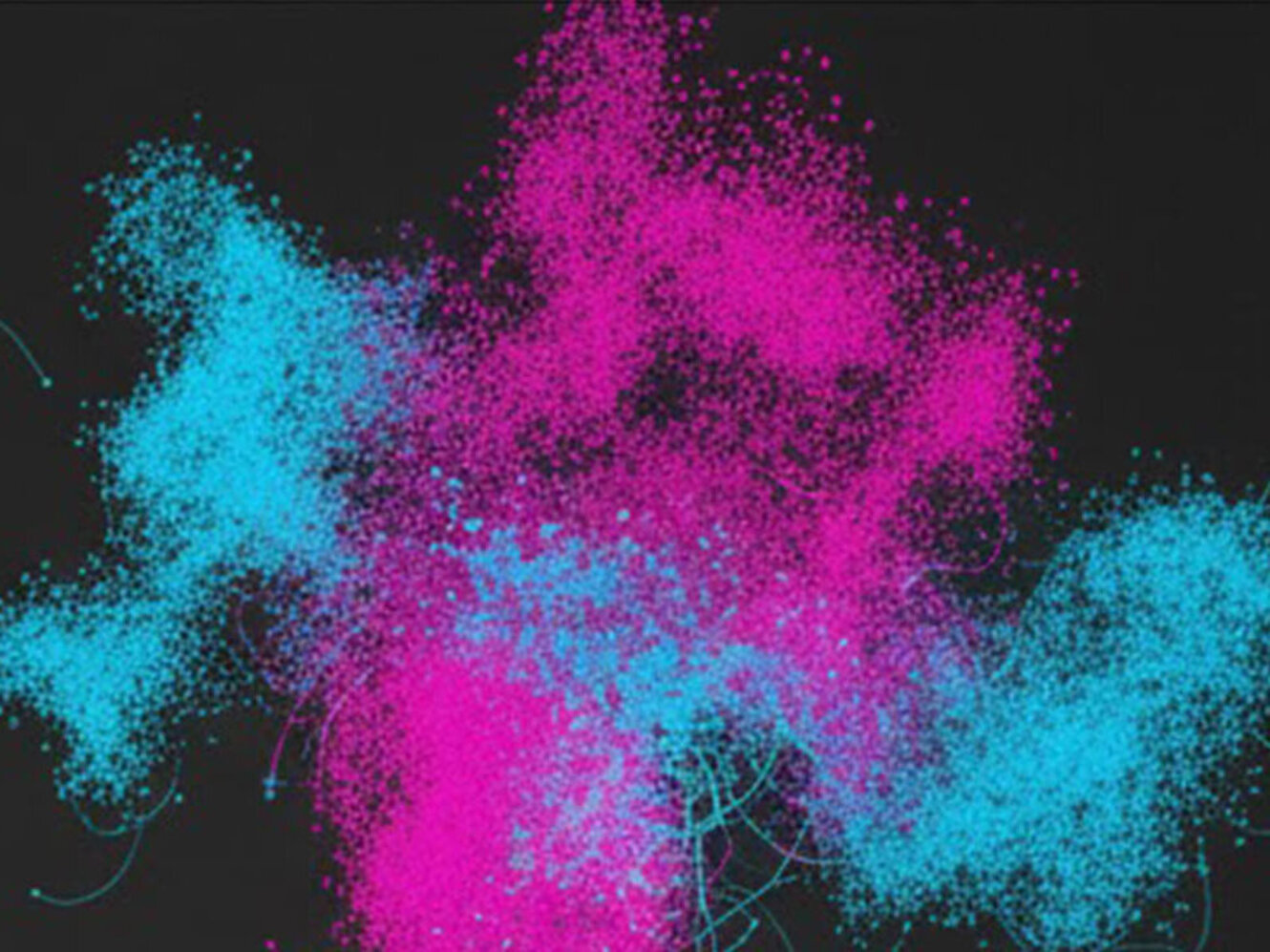

The spontaneous organization of matter into ordered, demixed phases typically arises from equilibrium thermodynamics, requiring inter-particle attractive or repulsive forces to minimize free energy. However, in Active Matter systems, phase separation can emerge from purely non-equilibrium motility control. A compelling, real-life demonstration of this phenomenon involves two strains of motile Escherichia coli (E.coli) engineered to exhibit reciprocal concentration-dependent diffusivity. The Theory of Complex Systems and Neurophysics Group (Benjamin Lindner) studied a system consisting of two species with sigmoidal (logistic) dependence on the other particle’s density. In their model, two states, a well-mixed and a demixed state, could coexist. A transition between the two states was induced by random pertubations. If you want to know more about the system with meatstability, read the article in Frontiers in Network Physiology.

Abstract

It has been shown before that two species of diffusing particles can separate from each other by the mechanism of reciprocally concentration-dependent diffusivity: the presence of one species amplifies the diffusion coefficient of the respective other one, causing the two densities of particles to separate spontaneously. In a minimal model, this could be observed with a quadratic dependence of the diffusion coefficient on the density of the other species. Here, we consider a more realistic sigmoidal dependence as a logistic function on the other particle’s density averaged over a finite sensing radius. The sigmoidal dependence accounts for the saturation effects of the diffusion coefficients, which cannot grow without bounds. We show that sigmoidal (logistic) cross- diffusion leads to a new regime in which a homogeneous disordered (well mixed) state and a spontaneously separated ordered (demixed) state coexist, forming two long-lived metastable configurations. In systems with a finite number of particles, random fluctuations induce repeated transitions between these two states. By tracking an order parameter that distinguishes mixed from demixed phases, we measure the corresponding mean residence in each state and demonstrate that one lifetime increases and the other decreases as the logistic coupling parameter is varied. The system thus displays typical features of a first-order phase transition, including hysteresis for large particle numbers. In addition, we compute the correlation time of the order parameter and show that it exhibits a pronounced maximum within the bistable parameter range, growing exponentially with the total particle number.