Symposium - Developmental Patterning in Space and Time

How do living organisms form complex structures from a single cell? How are shapes, patterns, and functions established and maintained over time? Developmental biology seeks to answer these questions by examining the interplay of genes, molecules, cells, and tissues — across different scales of space and time.

Our one-day symposium 'Developmental Patterning in Space and Time' brings together researchers from plant and animal systems to explore how similar principles underlie the diversity of life. Talks will highlight how positional information is generated, how dynamic processes drive pattern formation, and how developmental programmes evolve and adapt.

The programme features an exciting mix of perspectives and approaches, including:

- Floral architecture and plant morphogenesis

- Root development and plant–microbe symbioses

- Mechanical forces shaping tissues

- Molecular mechanisms revealed by spatial omics

- Comparative insights into patterning across kingdoms

With contributions from leading scientists in the field, the symposium will offer a platform for discussion, inspiration, and cross-disciplinary exchange.

We invite researchers, students, and anyone curious about the rules that shape life to join us for this day of science and discussion in the heart of Berlin.

Missed out on the event? Don’t worry — check out some visual and textual impressions from the day below!

More about the speakers...

Kerstin Kaufmann

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

The Plant Cell and Molecular Biology Group investigates how genes are controlled during flower development by integrating epigenomics, proteomics, and genetics to understand multicellular development on a systems level.

Caroline Gutjahr

MPI of Molecular Plant Physiology

The Mycorrhiza and Root Biology Group investigates the molecular factors that influence the formation and function of mycorrhizal symbiosis, exploring how environmental factors and specific molecules impact this process in both plants and fungi.

Arun Sampathkumar

MPI of Molecular Plant Physiology

The Plant Cell Biology and Morphodynamics Group studies how plant cell walls and the cytoskeleton influence growth rates and directions, while also managing a technology platform to assist other research teams with advanced imaging techniques.

Elias Barriga

TU Dresden (PoL)

The Biophysical Mechanisms of Morphogenesis Group explores the finely coordinated collective behaviors of cells during tissue development, focusing on how biophysical stimuli like mechanical and electrical forces govern processes such as migration and differentiation.

Jan Philipp Junker

MDC - BIMSB

The Quantitative Developmental Biology Group investigates the mechanisms of cell fate decisions in health and disease, using advanced single-cell genomics methods to study embryonic development and adult tissue regeneration in zebrafish.

Nikolaus Rajewsky

MDC - BIMSB

The Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Group investigates how RNA regulates gene expression in health and disease. They use a variety of model systems, including C. elegans, planaria, mice, and human brain organoids to study brain diseases in collaboration with clinicians.

Francisca Martinez Real

MPI for Molecular Genetics and CAPB (Spain)

The Gene Regulation and Evolution Group investigates how changes in the non-coding genome translate into developmental phenotypes during evolution using cutting-edge technologies and inter-species comparative analyses.

Teng Zhang

University of Helsinki

The Asteraceae Developmental Biology and Secondary Metabolism Group studies the gene regulatory networks in Gerbera that control the unique flower structure of the Asteraceae family. Their research also aims to understand the biosynthetic pathways for family-specific secondary metabolites.

The Langenbeck-von Virchow-Haus was built in 1914–1915 as the headquarters of the German Society for Surgery and the Berlin Medical Society. It bears the names of two outstanding physicians: Bernhard von Langenbeck and Rudolf Virchow. In the first few decades, the building served as a central meeting place for medical associations. After the Second World War, it was initially used by the Soviet occupation authorities, and from 1950 onwards it housed the People's Chamber of the GDR. During this period, important political decisions and elections took place in the building. After reunification, restitution proceedings were initiated, which were completed in 2003. The building was returned to the medical societies and underwent extensive renovation in 2004–2005. Today, the Langenbeck-von Virchow-Haus once again fulfills its original purpose: it is a modern center for medical meetings, training courses, and conferences, as well as an important architectural monument with a rich history.

In this beautiful setting, speakers and guests of the symposium gathered and admired the stunning architecture of the venue. The initiator and organizer, Kerstin Kaufmann, opened the event with a short introductory lecture in which she presented the theme and goals of the symposium, shared insights into her own research, and explained why the floral ground plan serves as a valuable developmental model system.

The first guest speaker was Caroline Gutjahr, an expert in plant–microbe interactions. In her talk, she introduced the audience to her group’s fascinating work on mycorrhiza — the symbiosis between soil fungi and plant roots that is essential for plant growth and health. She explained how her research explores the molecular factors that regulate the formation and function of these interactions, including how specific plant and fungal genes communicate to establish the symbiosis. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to improved crop resilience, nutrient uptake, and sustainable agricultural practices, demonstrating the broader ecological and practical significance of her work.

This was followed by a much-welcomed coffee break, where participants enjoyed drinks — including the long-awaited coffee — and light snacks. The break also provided an excellent opportunity for networking, exchanging ideas, and forming new connections.

After the break, the focus shifted from the molecular basis of development to the cellular scale. Arun Sampathkumar presented his research on the cytoskeleton and cell wall–based regulation of floral morphogenesis, illustrating how genes guide the formation of specific cell shapes. He explained how the geometry of cells provides directional cues for intracellular components essential to flower development, enabling the transition from a simple convex surface to a highly intricate, convoluted structure. His talk highlighted the sophisticated interplay between genetic regulation, cellular mechanics, and tissue architecture in shaping floral organs.

Offering yet another perspective on the question of shape, Elias Barriga explored how and why immobile cells can transition into collective groups that move together through space and time as a coordinated unit. His 'migrating images' evoked the movement of birds in the sky, shifting and reshaping as if they were a single body. He discussed the triggers that initiate this collective behavior and the mechanisms that regulate it, shedding light on how coordinated cell migration contributes to tissue formation and morphogenesis. Understanding these collective behaviors could provide insights into wound healing, organ development, and pathological conditions such as cancer, where similar coordinated migration plays a critical role.

After lunch, Jan Philipp Junker shifted the perspective toward the field of transcriptomics. Under the theme of reconstructing developmental trajectories from single-cell RNA sequencing, he presented an innovative method that repurposes the CRISPR/Cas9 system for lineage tracing. By introducing genetic barcodes into single cells, his team can track the fate and developmental paths of individual cells over time. This approach provides powerful insights into cellular plasticity, particularly in the context of neuroblastoma, where it helps dissect how both the current environment and a cell’s past history shape cell fate, influence malignancy and ultimately disease development.

Nikolaus Rajewsky, originally trained in developmental biology, now primarily works in systems biology. His research centers on 'spatial omics', an approach that combines single-cell sequencing data with spatial context to reconstruct the organization of tissues. Each cell is transcriptionally unique, and his team uses probabilistic optimal matching algorithms to assign cells to their correct positions. Applied to lung cancer tissue, this method can recreate the full tissue architecture, predict molecular mechanisms, and ultimately enable personalized, mechanism-based drug target predictions.

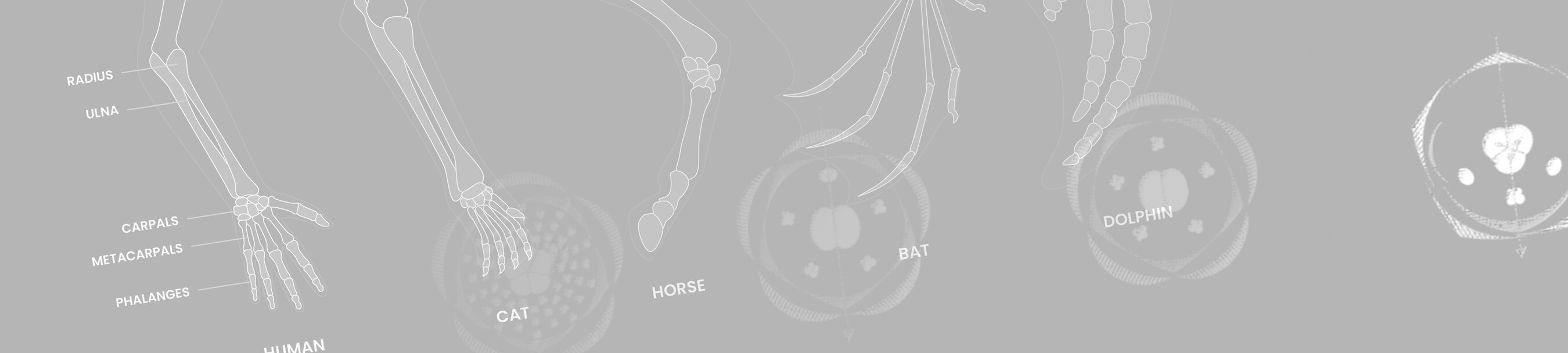

Francisca Martinez Real took the audience into an entirely new area — the emergence of mammalian flight and the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of the physical structures required for it. Her research focuses on bats, and to understand how limbs develop into structures with very different functions, she compares mice and bats to identify both conserved patterns and species-specific adaptations. Using an integrated inter-species limb atlas, she can visualize homologous cell clusters to uncover how wings form. Similar to the development of hands, paws, and fingers, apoptosis removes cells to separate digits. In bats, to form the Chiropatagium, this process is followed by the replacement of the dying cells through fibroblasts, creating the continuous skin layer essential for flight. Fascinating isn't it?

Teng Zhang closed the symposium by bringing the focus back to plants, specifically the diversification of floral ground plans in angiosperms. He shared insights from his work on the woodland strawberry, highlighting how floral patterning evolves. A key process he discussed is phyllotaxis — the arrangement of leaves or floral organs around a stem — which reaches its greatest diversity in the flower. These floral structures can become highly complex, forming spirals, whorls, or combinations of both, shaping the intricate organization of petals, sepals, and other floral organs. Following the transitions in phyllotactic patterning is not only fascinating, it also reveals how organs are precisely positioned during development. This insight helps explain the diversity of plant structures and can guide efforts in crop improvement or synthetic biology.